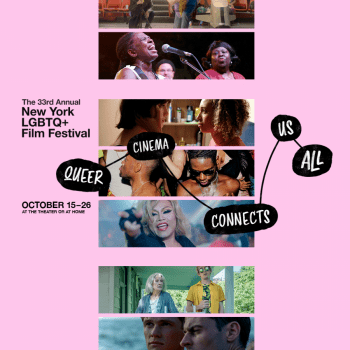

P.S. Burn This Letter Please

A Q&A With the Directors of The Iconic Queer Film Set to Premier at The Delayed Tribeca Film Festival This Month That Gives a Never-Before-Seen View on 1950s Drag Culture.

Dear Freshfruits,

In honor of the film that we feature in this article, we decided to write you a letter. It seemed apropos. Afterall, like “P.S. Burn This Letter Please,” things written in script that are personal, dear and heartfelt hit differently.

Whatever plans you have made on June 18th, I encourage you to toss them. NYC Pride will be presenting a cinematic event you won’t want to miss. Think “Paris is Burning,” but then subtract another 40 years or so. Virtually released in 2020 at the Tribeca Film Festival, “P.S. Burn This Letter Please” is a film that explores how a band of female impersonators and female illusionists, that we today refer to as drag queens, did the honorific thing of existing. At a time when many would think it was not vogue to be queer, to be out, to defy gender norms, and during the height of segregation, we see a unique look at how our queer foreparents contended with a society that didn’t always love them.

While it is typical of this time for families to burn letters, diaries, or any record of the “sins” of their children which could not be named, directors Michael Seligman (award-winning producer of “RuPaul’s Drag Race” and “True Hollywood Story”) and Jennifer Tiexiera (acclaimed and decorated producer and editor of “17 Blocks” and “Dragonslayer”) give life to an uncovered trove of letters that allow us this extraordinary look in the soon-to-be released film.

When famed Hollywood talent agent and a former executive of the William Morris Agency, Ed Limato, passed away in 2010, he left behind a number of letters from the 1950s in a storage unit addressed to Reno Martin, his nom de plume back when he was a radio disc jockey. It seems before Reno represented the likes of Denzel Washington, Mel Gibson, Diana Ross, and Richard Gere in L.A., he held court with a different group of local celebrities that included names like “Dayzee Dee,” “Rita George,” “Josephine,” and “Daphne”—female impersonators and sisters in spirit he had befriended in New York City.

This outstanding film takes us back via recitation of the letters and the personal accounts of those “queens” that are still alive, one as old as 94 years, and still donning the occasional dress and wig, although maybe a kitten heel! It also presents archival footage that is surely to be treasured, giving us a view into this time that historians have mostly only been able to study through police and hospital records.

What is most surprising about the film is that it challenges the misconception that queer people were mostly seen as pariah and presents a more nuanced look. It was very common then that luminaries like Liz Taylor, the Kennedys and Judy Garland would patronize establishments, like New York City’s Cork Club and Club 82 and watch a drag show that included live theatrical performances where the talent would be expected to sing in their own voices. Rather than show the darkness of this time, “P.S. Burn This Letter Please” is a moving and joyous film that preserves queer culture and cultural icons who otherwise would have been lost to time.

We sat down to chat with the directors of this extraordinary film that will be getting wider distribution later this month on Disney+, On Demand and will be available on iTunes and Amazon Prime. Make sure to visit our events listings page, where you can schedule the event in your calendar, so you don’t miss it.

Love always,

Freshfruit

P.S. Please don’t burn this letter…

Interview with directors: Michael Seligman (award-winning producer of “RuPaul’s Drag Race” and “True Hollywood Story”) and Jennifer Tiexiera (acclaimed and decorated producer and editor of “17 Blocks” and “Dragonslayer”)

Wesley: How did you discover the letters and this extraordinary story?

Michael: Two of my very good friends Craig Olsen, who’s a producer on the film, and Richard Konigsberg, who’s executive producer, are a couple, and they were good friends with Reno Martin. They were put in charge of the estate of Ed Limato who figures in the film, and after he died, he had a lot of stuff that needed to be gone through. In 2014, they found this box in the last storage unit and it had all these letters in them. They started reading the letters and thought, “Oh my gosh, these letters are written by drag queens in New York City in the 1950s.” So, they called me. I have a background in TV and research and all that, and so we just started looking into this history and being super curious. All of us are gay, so, we were especially interested and started piecing things together, making phone calls, calling archives, calling historian and everybody was just so impressed by this discovery because it was so unique.

Wesley: How did they come to know Reno?

Michael: Reno was this popular figure who grew up in New York City and moved to New Orleans when he was a young man to pursue a radio career. His friends, clearly, wanted to stay in touch with him and keep him apprised of their goings-on and so they wrote letters. It’s the 1950s, long distance phone calls were very expensive, and letter writing was pretty common. Fortunately, Reno kept the letters for 60-some odd years. They were clearly important to him on some level.

Wesley: Was Reno gay?

Michael: Yes

Wesley: How did you go about tracking down each of these characters?

Jen: It was a lot of persistence. Obviously from the letters, there was not a lot of information. They use their drag names just in case their family were to find these letters. So, we had drag names, we didn’t have the return addresses. There were just the letters; maybe there was a mention of an address, maybe we had a birthday. So, it was a lot of just piecing together. We enlisted the help of a PI (private investigator) to get us these lists: “this is all the “Claude Diaz’” that were between this age in the country that lived in New York during this time.” So, we started calling. Every once in a while, we would get a hit, and obviously, Claude’s in the film. Every little piece took so long to uncover. It wasn’t like things were falling in our lap. When we started the process, I think what initially drew all of us to this film and this project was the fact that there was nothing. There was nothing in the 1950s besides these police records and these hospital records. Once we started discovering or getting in touch with them, they’d be like, “Oh, well, we heard that so-and-so is still alive.” Then we could track him down. Our queens are not very tech savvy. They don’t have cell phones; they have land lines. It was definitely a long process. The same can be said for the archival searches. We have a lot of never-before-seen archives in the film, and that was just as much of a search as it was for the people.

Wesley: Were there other people that you could not find, or did you include everyone that wrote letters, essentially?

Michael: When we read the letters there were at least a dozen and a half letter writers, maybe. The ones that were really prolific, though, and really colorful and really stood out to us initially were Daphne and Josephine and Billie and Charlie. We kind of focused on them. The other ones, we either couldn’t find them, or we heard from somebody that they passed away.

Wesley: So, here you have accounts of people that are alive and some who aren’t. How did you decide to structure this? How do you then imagine what this should look like?

Jen: We made a couple of really big decisions up front. First and foremost being that we wanted to fill in this piece of history. As one of our amazing queens pointed out to us when she was trying to understand the process of the film, she’s like, ”Oh, you’re not telling my story per sé, you’re telling these stories.” That was really eye-opening for us. We wanted to create this time that had basically not been written down or that had actively been destroyed (burning letters and stuff like that). Additionally, there’re so many amazing films out there that really focus on the darkness of the gay experience and the letters weren’t that. The letters were joyful, and beautiful, and celebratory, and full of love and crazy, high jinks. We wanted to make sure that we didn’t lose that completely, because that was obviously part of that time and what these queens experienced and what makes them so heroic. It’s structured around moments of discovery and joy and excitement and silliness. Those were [what] guided our narrative.

Wesley: The subjects of the film considered themselves either as a “female impersonator,” “female illusionist” or “femme mimic,” unlike today’s drag queens. What is your understanding of the distinction?

Michael: In the 1950s, the people who were performers, who got paid to do drag, were the ones that considered themselves artists and would call themselves female, Illusionist, female mimics and they were performing an artform. And they were really good at it. They had talents. They had singing abilities, or they had the ability to do comedy, or dance, or they might perform in a club. I think that there was among them a level of distinction that they were artists and they wanted to consider themselves in a particular category. In those days a drag queen was like somebody who would get dressed up and on a Friday night and go to a bar and hang out or go to parties and just kind of perform for their friends and they weren’t “professionals.” And sometimes there were people that would turn tricks and dress up in drag as a means to make money in prostitution, as Claude talks about. Over the years we’ve sort of lost that distinction. Certainly, it’s no shame to be called a drag queen, but I think in the 50s the upper echelon were like, “Please don’t call me drag queen. I’m an Illusionist.”

Wesley: Your film preserves not only the story of the living legends, but the history of the time that includes popular bars such as the “Cork Club,” Club 82,” and “Wagon Wheel,” a period of time when there was some level of integration of drag culture in high society. What surprised me was that it challenged the historical narrative where drag queens and queer people in general were seen as pariah when in certain circles it wasn’t just tolerated but embraced. Is that a fair assessment?

Michael: George Chauncey is one of our historians talks about in his book “Gay New York” that there were these myths about gay life before Stonewall. I think on some level that those myths have been purposely propagated in an effort to denigrate gay history and gay people. When you disconnect a person from their heritage and from their history, you don’t give them idols, you don’t give them role models and people to look up to. And so, by kind of burning books, burning letters, burning diaries, actively writing gay, people out of history or writing them into history in a way that is sad and pathetic, you can really do harm to an entire community of people. What was so exciting was to not only read the letters, but then to find the people from this time period and realize they were very well-adjusted: they knew exactly who they were, they had no shame in who they were, they knew the limits that they could operate in a society that was very much against them. But they learned how to find joy in life as happily adjusted out, queer people. That was such a beautiful thing to discover that there certainly were a lot of dark days for a lot of queer people for many decades and centuries and even today. But to know that gay people have always found a way to find happiness and find love. A lot of the people in our film had very long successful relationships for decades. You just think, “How could that have been possible?” So, to be able to rewrite some of that history is really exciting for us.

Wesley: Can you speak to the importance of the preservation of the vernacular? Through the letters we learn terms of “mopped it,” “mop on it,” “mopped,” “trade,” “number,” “dish,” “Susie, ” and “cunty,” some of which live on today but others that have not. The queer community influences culture, including through language, which your film highlights.

Michael: When you talk about drag culture, there’s no handbook. There’s no definitive guide to becoming a drag queen. This culture is passed from drag mother to drag daughter. The fact that so much of the language has survived very much intact. When we were reading the letters, I was like, “I know what mopped means, you know because we still use that today on TV shows like “RuPaul’s Drag Race.” It’s really another testament to the perseverance or the way that gay people have been able to preserve our culture from generation to generation. This is not something that you learn in school, or in a church, or mosque, or a synagogue. This has passed on from peer to peer and is quite impressive.

Wesley: The drag ball, as the film discusses, was a unique place of integration of race and sexual orientation and that provided a non-judgmental environment, but I wonder how strongly class played a role

Jen: The Harlem section needs to be its own film. It absolutely warrants its own film and there’s even less about the balls in Harlem than there is about the rest of this. I don’t think we can really talk about any of this without the conversation about class, even our queens would work at these mob-owned drag clubs, but it was still this upper class that came to watch them for entertainment. The balls were the same way. They had a special license for one night, but it was a form of entertainment for the people to come and watch all these queens come out.

Michael: What was so unique about these drag balls is they would attract crowds of thousands. Harlem was one of the locations that was welcoming and had the ability to have these things outside on the edges of the city, not in the central parts of the city where there was more police activity and tourism and stuff like that. There was an effort at some point by New York City to push all the queers to the fringes of the island, so that when tourists came, they weren’t horrified and wanted to leave immediately. So, these drag balls were allowed to flourish in places and because of that you have this mixing of races in particular events at a time when most of the country was segregated. I don’t know if it is a testament to the art of drag or to the people themselves, but it’s just very interesting that these venues were places where races were mixed without a lot of issue.

Wesley: It was very heartening to see the characters reminisce of a bygone era, how their friends were ravaged by the AIDS epidemic, and through it recognize their contribution to the movement and further acceptance of queer culture. What has been the general feedback from those featured in the film?

Jen: I think they’re still realizing that. We’re still trying to convince them of that. We have our premiere coming up finally. We were supposed to premiere last year at Tribeca. Obviously, Covid postponed that till this year. We’re finally having some of our queens join us at this premier. They all collectively say, “We were just being ourselves. We’re not sure how this is heroic or revolutionary in any way. Michael and I’s hope is that when they see that our premier sold out in less than three minutes, that people want to see them, people want to hear from them. I can’t wait for this Q&A. I don’t think they still understand the important contributions that they made. I think it’s going to be extraordinary.

Wesley: Why was it important for you to create this film?

Michael: It started out as a curiosity: “what could we do to make more of these letters?” In the early stages talking to people and discovering these people and realizing that everybody that we spoke to, from historians to people that work in archives, were so impressed by this and so motivating to say, “Keep going. Keep going. Do something. Do something.” I think it was just the momentum of it. Certainly, once we started finding these people, we needed to make this film while these people were still alive and while they could be honored in their lifetime for the work that they did. And you know what’s funny is, like Jen was saying earlier, talking to these people, we’re amazed and so impressed by their stories and how heroic we thought they were. And they were like, “We’re not heroes! We were just living our lives. Like, why are you so interested? Why do you care so much?” They couldn’t get over how much we cared about their lives and their stories. And we’re just like, “Are you kidding me? You are incredible! What you did in those days and the fact that you survived and thrived, we don’t have a lot of queer elder heroes that are still alive, that we can talk to you and ask questions to. The people in our film have become our family. As soon as we hang up, I’m calling Adrian to check up on him and make sure he’s coming next week. As queer people, our families aren’t necessarily biological people we’re related to. They’re the people that we find. We’re so lucky to find them.