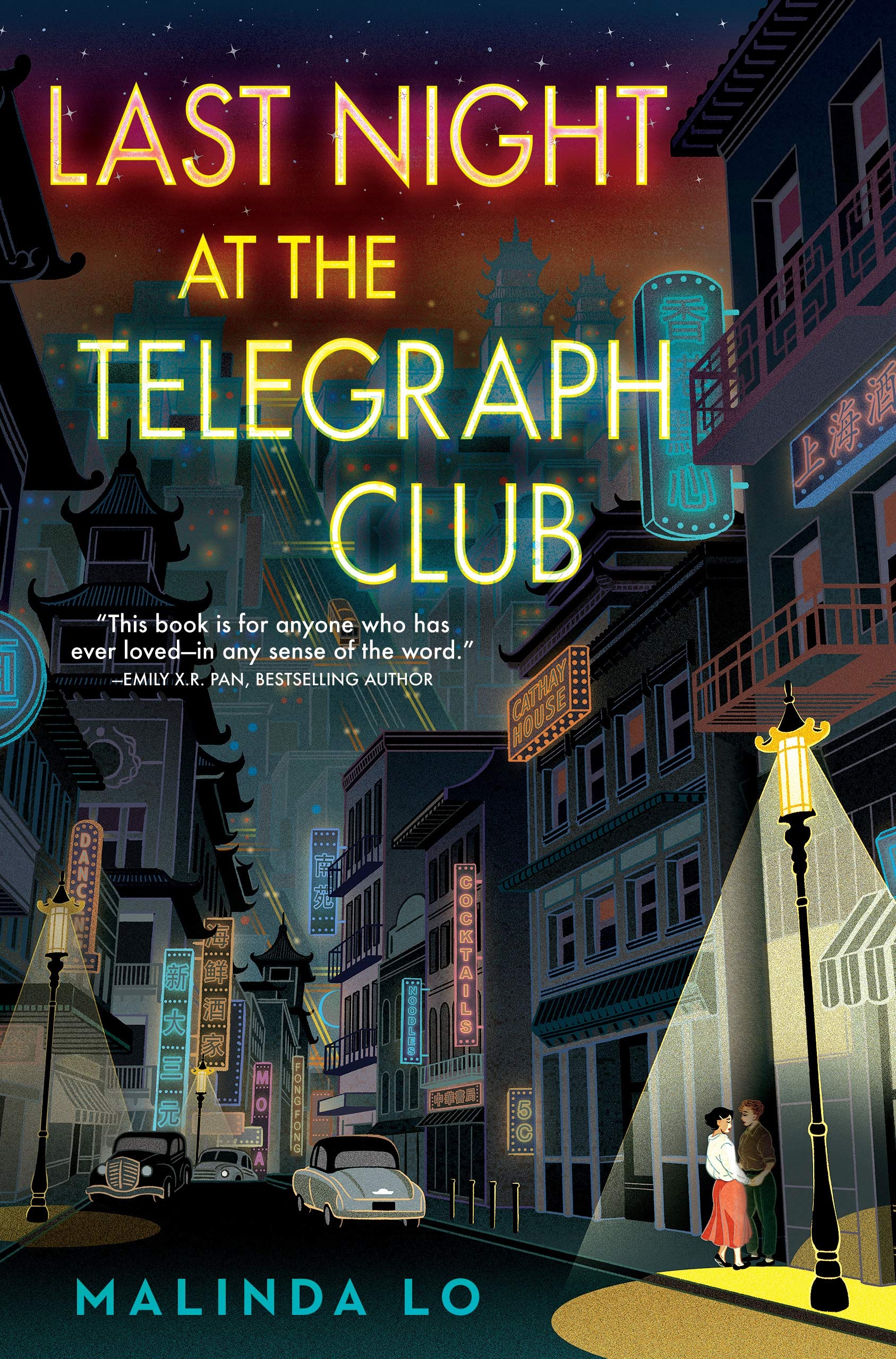

Last Night at the Telegraph Club

If you’re familiar with Malinda Lo you know she’s an old hand at adaptation, not only her own “Adaptation” duology, but also her queer Cinderella retelling, “Ash” and its prequel “Huntress.” She has also mastered the art of the short story, with over a dozen published in various collections. Lo’s newest work unites these two strengths into one stellar alternate history: her own. Based upon the short story, New Year (originally published in the YA queer anthology “All Out”), “Last Night at the Telegraph Club” expands upon that original idea, and is the closest she has ventured into autobiography, stating that “this book gave me the opportunity to imagine what a family like mine might have been like if they had stayed in this country”, rather than having returned to China in 1947 at the height of the Red Scare, and remaining there until 1978. A personal retelling, an historical fiction, a culturally diverse cast of characters, and the blush of a first love, this novel will be sure to captivate you.

Beginning after World War II, the Red Scare was a movement spurred by fear and paranoia of communist forces infiltrating the United States and spying for the Soviet Government. The strain of that constant tension on Asian Americans, primarily Chinese and Korean, wore daily, as threat of interrogation or arrest loomed over the entire community, regardless of their political affiliation. It is also relevant to keep in mind that in 1954 a series of hearings centered on McCarthy included inquiries concerning the threat of homosexuals in government.

It is with this backdrop that Lily, a Chinese American living in San Francisco’s Chinatown, begins to question several things about her life: her safety, her friendships, and her sexuality. When her best friend Shirley begins attending meetings with a group that is under investigation for their ties to communism, Lily’s parents have to warn her against spending time with anyone that might draw further scrutiny to her and her family. It is especially dangerous now that Lily’s father, a doctor, was questioned about the political affiliation of a patient of his, and after refusing to answer questions, had his citizenship paperwork taken from him, threatening possible deportation. Distancing herself from Shirley gives Lily the opportunity to pursue a friendship Shirley had pressured her against, one with Kathleen Miller, the only other girl in Lily’s math class.

Something about Kathleen intrigues Lily. Spending time with her gives Lily the same feeling as seeing two women sitting closely in a booth, or the advertisement in the paper for a show featuring Tommy Andrews, male impersonator (that’s Drag King, for those of you who don’t speak 1950’s queer). When Kathleen mentions she’s familiar with The Telegraph Club where Tommy Andrews performs, Lily musters the courage to ask if Kathleen will take her to see the show. The performance in equal parts captivates her and terrifies her, and while Tommy Andrews performs “Bewitched, Bothered, and Bewildered” (listen to Ella Fitzgerald’s version when you read this the first time, you won’t regret it), Lily begins to see a version of a life she’s never known could exist before: one in which women can be happy in relationships with each other. But is that happiness something that Lily will be able to achieve, already under heightened scrutiny as an Asian American? And she’s not sure Kathleen even likes her like that.

The Telegraph Club becomes Lily’s regular hangout; a place where she begins to understand the dynamics that can exist between women, both friends and lovers, and ventures into letting herself feel those things rather than observe them from a calculated distance. When Shirley comes back into Lily’s life, asking that they finish out their senior year the way they started their kindergarten, together, Lily knows she must keep the Telegraph Club a secret. Her management of a double-life elicits comparisons to the subterfuge of possible foreign operatives, and Lily is confronted with the fact that both she and Shirley are keeping dangerous secrets from each other. These secrets inevitably surface, Shirley and Lily both knowing they need to continue to be discreet about their respective affiliations. However, when the Telegraph Club is raided one evening when Lily and Kathleen are there, Lily is spotted fleeing the scene by someone in the Chinatown community, and Shirley is the one who confirms the rumors to Lily’s parents. It is in these tumultuous scenes following the raid that it becomes clear that “Last Night” is as much about how a community can support you as how a community can threaten you, and who gets to decide which community prospers.

The history and the present are often illustrated as being closely tied together, with chapters that focus on Lily’s family. In showing how related her past is with her present, it also asks us to think about what America of 1954 has in common with America today. The chapters which flash back consistently have tie-ins with Lily’s current life. When in one chapter we hear from Grace, Lily’s mom, that Chinese women kiss “with their fingertips instead of their lips”, the following chapter tells us that “Kath’s fingers pressed lightly against Lily’s upper arm.” When in flashback, Lily’s aunt Judy takes her to the planetarium Lily feels as though she’s been transported to another world just by the images of the sky alone, but when in the next chapter Lily learns of the Sky Tram, she wonders who would want to see such a thing, moving without going anywhere at all. The past informs the present, fights against it, and learns from it in every section of this novel.

If you are wary of not knowing the finer details of the Red Scare, or how it might be informing the story and its events, Lo adds timelines in the chapter breaks which situate our characters and their lives within the greater framework. She does not require you to be versed in the history, just familiar with the feelings: fear, paranoia, uncertainty. After Lily’s parents sit her down to warn her about questions being asked about a gathering she attended with Shirley, Lily is confronted with some hard questions of her own, but so too are readers. What makes “a proper American family” and how can that be made clear? Lily wonders how to act, what to say, and how to be to prove that she is American, bringing to mind the kinds of conversations minority parents continue to have with their children to ensure their safety. When Lily then begins coming into her own understanding of her sexuality, the same questions resurface with a new context: in what ways might she be making her sexuality obvious to observers, how can she act and what can she say to be visibly queer when it’s safe to be but otherwise not arouse suspicion?

This is not a book without consequences, for any of its characters, and it strikes the delicate balance of being realistic about where it is historically situated without swinging too far on the pendulum between hopeless and indulgent. The casual racism and homophobia that peppers the narrative feels dutiful without being played for shock or sympathy or being dwelt on for too long. And if by the end you are still uncomfortable with its inclusion in this book, or curious about why a particular word was used, or what was actually happening in Chinatown in 1954, all you have to do is keep reading! Malinda Lo has included a generous author’s note at the end of this book that will allay any unease, addressing the culture, the language, the setting, the queers, and rounding it out with a two-page selected bibliography and documentary film suggestion, so you may never be done with this book. And who doesn’t want their TBR expanded, especially at the beginning of a new year?

“Last Night at the Telegraph Club” is out January 19th, but if you need something to read in the meantime, Lo’s other works are available now, and they’ll certainly tide you over until this gem arrives.

About this book

- ISBN:9780525555254

- Price:$18.99

- Page Count:461

- Genre:Young Adult

- Buy Now