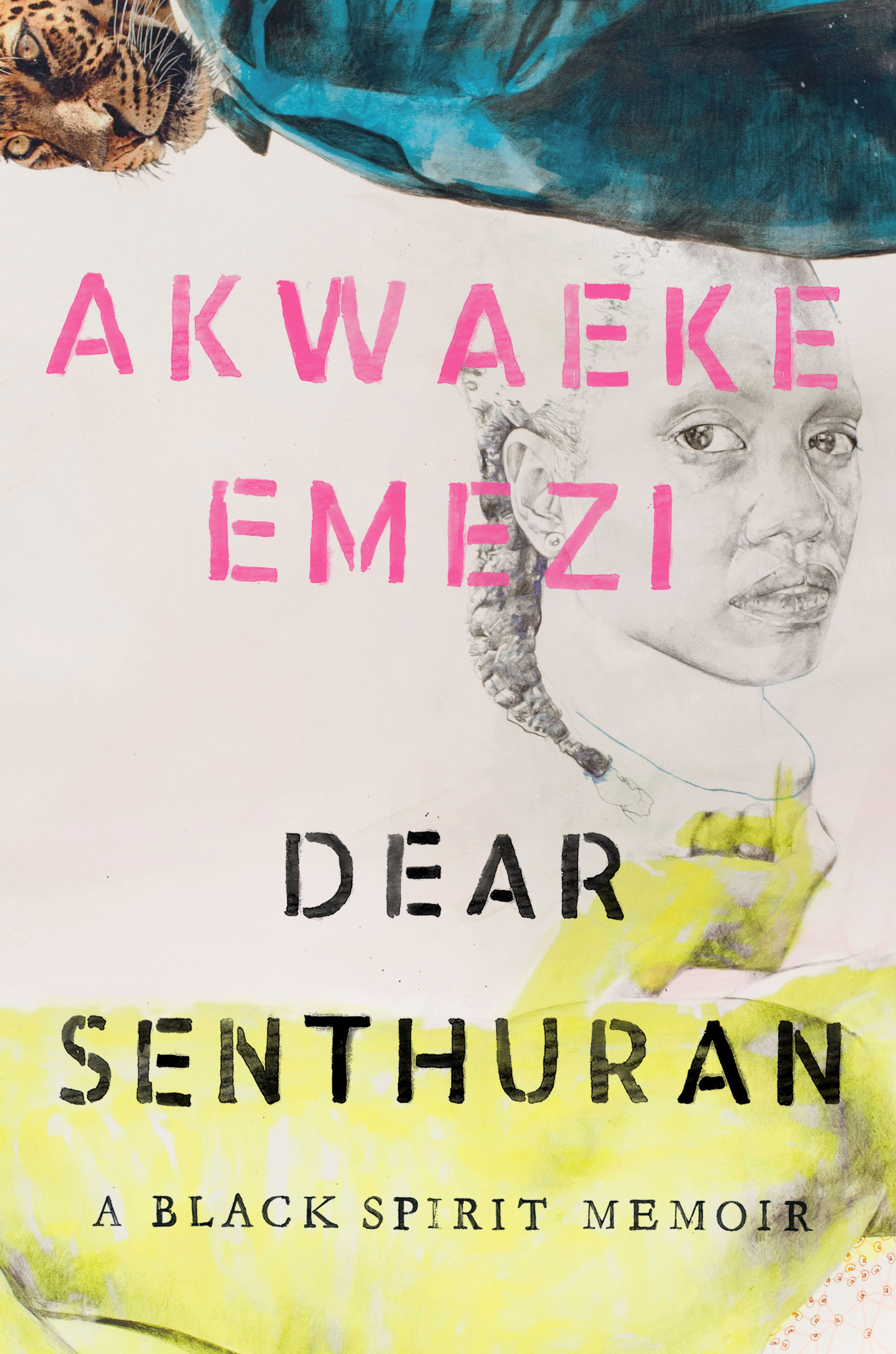

Dear Senthuran: A Black Spirit Memoir

I don’t believe in God. But I believe in Akwaeke Emezi, and so perhaps I need to rethink what a god is, and what a god can be. Emezi’s newest publication, “Dear Senthuran”, is a series of letters addressed to various people throughout their life, each grounded in a specific theme, telling the story of Emezi’s metaphysical coming-of-self. The letters deal with the dysphoria of being bodied as an ogbanje (don’t worry – I’ll get to it) and the journey of reconciling with the manifestation of that body. It is about contending with grief and anger, of moving with certainty, and of moving towards a reality in which they can live by an Alexander McQueen quote of not caring what other people think of them, nor what they think of themselves. “Dear Senthuran” is Emezi’s fourth book, and if you’ve read their others, some of this will already sound familiar. If you haven’t yet, “Dear Senthuran” won’t be released until June 2021, so you have time to familiarize yourself with and worship at the pen of the God that is Akwaeke Emezi.

“Freshwater”, Emezi’s first book, is a novel that is based in the reality of the author’s lived experiences of existing as a fractured self, steeped in Igbo culture and traditions. “Freshwater” has a starring role in “Dear Senthuran” and it’s referenced often as a prominent touchstone in their embodied life, all through its path to being written, published, received, and celebrated. But it’s the conversations that “Freshwater” started that are continued and rebutted in these letters. While knowing the original text isn’t necessary to learning about Emezi’s experience creating and sharing it, it doesn’t hurt to have already tread some of this queer ground, and there is a lot to cover. In many ways, “Dear Senthuran” is a way to build upon the truths that were used in the fiction of “Freshwater,” and expand on how Emezi has come to terms with her non-human-ness. Because of the similarities of the Igbo understanding of ogbanje and the psychological understanding of multiple personality disorders, “Freshwater” was interpreted as a metaphor for mental illness. Emezi makes sure to be explicit about the decolonization that had to happen between having “Freshwater” be read through a western lens, and insisting in “Dear Senthuran” that their entity be recognized, if not worshiped. “When the press for Freshwater began,” Emezi writes, “ I made NPR acknowledge my multiplicity of self on air, made the press use plural pronouns, centered Igbo ontology as a valid reality made unreal only by colonialism.”

Emezi is a small god, working towards allowing themselves to be a big god. This is neither hyperbole nor metaphor, it is no more or less than identity, rooted in the Igbo understanding of ogbanje. “An ogbanje,” Emezi writes, “is an Igbo spirit that’s born to a human mother, a kind of trickster that dies unexpectedly, only to return in the next child and do it all over again… Ogbanje come and go. They are never really here.” Emezi is an ogbanje, birthed from a mother that they call their “excellent guardian,” the human surrogate to the deity that is their predecessor. This is the identity which is at odds with the human flesh, the person-shaped container Emezi is forced to wear while of this world, before being allowed to return to the collective ogbanje spirit world from which they came. Emezi muses in an early letter that while standing at the foaming edge of the ocean, they might dissolve “and be withdrawn into something vaster than my immediate body.” With “Dear Senthuran”, they are creating that vastness, and showing that a becoming of that magnitude does not happen while waiting, but rather must be worked towards.

Part of Emezi’s journey to work towards that magnitude includes two surgeries to align their vessel with their spirit: a breast reduction surgery which includes nipple removal, and a subtotal hysterectomy with a bilateral salpingectomy (a removal of the uterus and fallopian tubes). This was not only a physical necessity, but as Emezi explains, “After that first surgery, my depression lifted significantly. It was a connection I hadn’t made before, how that physical dysphoria was affecting my mental health.” There is a shift, throughout the letter writing, from focusing on the physical to focusing on the spiritual, the experiential, the otherness and how it is manifest, how difficult it is to express. “For embodied nonhumans, existence is more difficult than I can ever put into words, no matter how many books I write,” they explain. But these thirty-three letters make it a little clearer at least.

If you’re not a small deity or haven’t encountered one before, you will still find in these letters a truth that you will recognize. For as much as this is about embracing spiritual disembodiment, it’s also a series of letters about heartbreak, something you might guess a nonhuman would have less trouble with than others, but Emezi proves otherwise. The magician is a recurring person in Emezi’s narrative, a man Emezi was in a relationship with until it ended due to his infidelity. The magician is the figure through which Emezi examines loss, time, anger, betrayal, and desire, among other human emotions. He weaves his way through each of these letters. His presence is often used to explore what it means to have emotional feelings as a human—even when you’re not one exactly. It’s with the magician that this collection of letters begins and ends, a figure at first romantic, eventually made irrelevant through Emezi’s embrace of their own metaphysical reality.

The magician is not the only recurring figure. Many of the addressee’s in this collection receive more than one letter, some as many as three. The titular letter, Dear Senthuran, is one of the few people to whom Emezi writes only once, and is one of the people to whom Emezi appears to be speaking with directly. Emezi writes that they mostly chose Senthuran’s name for the title because they liked the way it sounded, absolving readers of the need to delve deeper into that particular section. There does appear to be some inconsistency in the personalization of these letters; some touch on shared memories, experiences, or identities in a way that illustrates the importance of those people in Emezi’s life, and others receive no personalization at all, easily read as chapters rather than letters. While I wonder at whether those to whom letters are addressed will get more from those sections than general readers, more context as to their role in Emezi’s life might have provided some insight into why these particular people merited a letter in Emezi’s first memoir. As it stands, however, only some of the addressee’s identities or roles can be gleaned from the text itself.

There are two letters in this collection addressed to Nonso, which appear to be written for the reader. Nonso, in Igbo, a language spoken chiefly in Nigeria, translates as “ever near,” derived from “Chukwu nonso” meaning “God is ever near.” The first letter, Muse, begins with “This letter is a naming that can be spelled as a warning,” and addresses what it means to have inspiration, how that becomes visible to other people, and how to stay focused and dedicated to the work, rather than the people who pull themselves close to the work. Those people, Emezi warns, will take what they can, and the work will be diminished, you will be diminished, because of their involvement. The second letter, Money, begins “This letter is a record; I want to be transparent about as much of this industry as I can. Publishing can be so opaque, so human, full of invisible rules. I hope this record is helpful to writers coming after me.” This letter is its own #publishingpaidme confession, thorough and condemning and proud where people are often bashful or secretive. It chronicles the timelines and paychecks of their first books, in a way that is almost never shared with the public, and reads as a revelation for those with no experience with writing or publishing a book. Each of the letters addressed to Nonso have a specific purpose, a particular message that Emezi felt readers and writers should know, and each succeed in their objectives.

So, too, does the book itself. The making of an entity, the unmaking of a body, the translation of a spirit not only into language but across cultures, all achieved in such a short volume. “Speaking to other people, though,” writes Emezi, “requires channeling who or what I am into language they can understand. It requires unfolding.” “Dear Senthuran” allows us to witness just such an unfolding, and Emezi is the only author I would trust to unfold so precisely, with such honesty, not caring what you think of them, and hopefully not even caring what they think of themselves. Who wouldn’t want to read a book written by a god?